Interview with Max Yeshaye Brumberg-Kraus about their book The(y)ology

We discuss "advocacy for the many," queer and trans liberation, drag, ecology, feminist philosophy, queer theology, and much more.

In an era when the “self” is often encountered via front-facing cameras, compacted and diluted into the superficial variation of “personal brands” across social internet platforms, and exploited into time sold as labor, it is no small thing to see our selves as part of a wider cosmos. Indeed, no small thing to recognize and participate in our selves as a cosmos. Rather than experience the self as an object to constantly upgrade, singular but incomplete, how can we practice new, better worlds?

Max Yeshaye Brumberg-Kraus’s The(y)ology: Mythopoetics for Queer/Trans Liberation invites us to play with myth – as method and something like worldview – to resist this tyranny of oneness, and access a liberatory multiplicity. Just as the title combines a plural, third-person pronoun and hints at many theological traditions, the book is invested in the “consistent advocacy of ‘the many.’” With monolithic hegemony enforcing myths of one true self, one sexuality, one gender, one true God, it is easy for deviations like queerness and transness to be othered, erased, and punished. Rooted in queer theologies, Brumberg-Kraus insists on interacting with the world and our selves as if the earth is all alive, and nothing and no person is ever just one thing. This is a book that gnashes its teeth at duality, chews it up, and massages the pulp to compost a plural, abundant subjectivity.

Instead of simply replacing one monolithic reality with another monolithic reality, Brumberg-Kraus provides several examples of what “aspiring toward the multiple” can look and feel like, and contributes frameworks for us not only to better understand the mythologies around us, but also encourage us to create our own mythologies. Across an intro and four chapters, they lean on feminist philosophy, ancient theatre, liberation theology, kabbalah, drag performance, and more. The last chapter shows us myth in action with an original “drag theopoetic.” “We form each other when we imagine together,” they say in the introduction. “Join the movement. Make a myth of your own.”

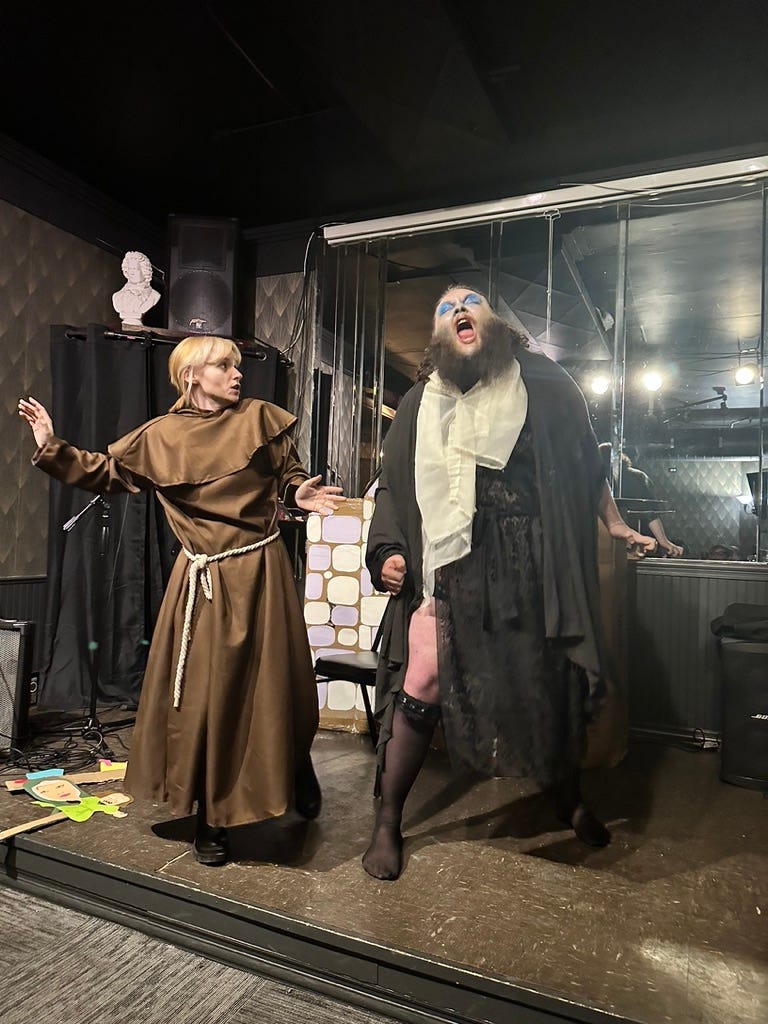

Published by para-academic press Punctum Books in 2023, the book began as Brumberg-Kraus’s master’s thesis at United Theological Seminary’s Theology and the Arts program. For Brumberg-Kraus, a writer, performing artist, and theopoet in Saint Paul, MN, their work as a theologian is intimately tied to their performance and artistic work. Trained in Classics and Theatre, they also co-founded the House of Larvae Drag Co-operative troupe, performing as drag ogress Çicada L’Amour. While the book is rich with theological and Classics references, they are also speaking to artists and queer and trans people who may or may not have a relationship to organized religion.

I sat down with Brumberg-Kraus earlier this year to talk to them about their book, which I think provides a unique – and juicy – orientation to the woes of late capitalism, with resonances for many different audiences. As someone without theological training, some of the references eclipsed me, but left me curious. And as someone with a background in environmental humanities, and a penchant for queer ecology, I appreciated Brumberg-Kraus’s clarity about the role of art and performance in contributing to collective material change.

Our conversation wound down many paths, and I wish I could include it all. Here, we talk about the evolving definition of myth, interdisciplinarity, generative tensions between Radical Feminism and trans liberation, their workshops in embodiment and shared gender biographies, alienation from religion and many kinds of community, art and activism, connections to climate change and ecological thinking, and much more.

If you haven’t read the book, it might be helpful to know what is meant by mythopoetics. You should read the book, but here is Brumberg-Kraus defining it using media theorist Patrick D. Murphy:

Feminist mythopoeia critiques the patriarchal world order – an unjustly established “real” – through the proliferation of fantasy worlds, that is, worlds on a continuum of imaginary distance from their proximity to current reality. The creation of myth is not a creation out of nothing but a practice of reinterpreting inherited mythologies by changing dominant stories or invoking their silenced perspectives or by uplifting the myths of those women suppressed by patriarchal religion, history, and literature.

Along with The(y)ology (punctum books, 2023), Brumberg-Kraus wrote the book for Mixed Precipitation's Pickup Truck Opera, Vol. 4: Faust (MN, 2024), a space-age exploration of Gounod's opera paired with the music of Depeche Mode; Circe: Twilight of a Goddess, produced on three floating stages by Siren Island at Point San Pablo Harbor, CA: and is the author of Visions of Divine's Love: a Drag Theopoetic (AC Books, 2024), a collection of poems that reimagines medieval mystic Julian of Norwich as receiving her revelation from none other than Divine the Drag Queen in John Waters's Pink Flamingos (1973). Brumberg-Kraus is currently working on another book inspired by Julian of Norwich: Art Anchorites: Co-Creating with a Medieval Mystic while also collaborating with their father, Dr. Jonathan Brumberg-Kraus, on a Thanksgiving Haggadah, inspired by the Jewish ritual of the Passover Seder. When not performing or writing, Brumberg-Kraus preaches, teaches, and leads on gender and spirituality, drag performance, and arts mentorship. You can follow their work at https://www.maxyeshaye.com/

Interview has been edited for length and clarity.

AD: One of the interesting things about this book is that you are playing with so many disciplines. How would you say that these modes – of performance, academic writing, creative writing, research – influence each other?

MBK: By and large, this is a constructive book: I'm putting things out there about how we could think about the world how we could act in the world, how we could talk about the world, how we can talk about ourselves and each other, and what is sacred. It's not primarily a critical text.

And the other thing is, you know, right in the title is a plurality, right? If there's really any theme that comes up chapter after chapter after chapter, is this advocacy for plural possibility, plural identity, plural intentions, plural meanings, all sorts of things, plural ways of performing and being in the world. So I think that naturally leads to an interdisciplinary approach.

I also just think that it would be silly for me to write a book about myth-making and to not make myths. I think that it didn't feel right to end on a fully interpretive or critical analytical ending when I think it made a lot more sense to end with something that feels more like a story to be interpreted, critiqued, thought about, engaged with in that level of story, rather than in that level of analysis.

I was hoping for a resolution of some kind, necessarily a resolution of all the ideas but a resolution between people. I thought it was better to show it, how I at least could see it and have someone who has some of the kinds of questions that maybe we're not supposed to ask.

AD: This book has so many resonances for so many different audiences: theologians, queer and trans studies scholars, queer people who have a relationship to religion or spirituality, and those who don’t, artists and performers of all kinds, as well as environmental studies folks, social justice organizers or activists, etc. What’s been the response so far?

MBK: The book was released in June [2023] which, you know, felt appropriate for Pride Month. I hosted an event [at] a gay bar that let us use their space to do an event.

And this is kind of a model that I would like to do going forward with this book is, I read a section from the book and then I had a panel of artists [respond]. It was not a group of primarily like people in grad school or in academic fields. So visual artists, performance artists, dancers, poets, singers, textile artists.

[The audience] was pretty mixed between people who are artists, people who are neither artists or academics but are queer and excited about this, friends, parents. One person… was so worried that she wouldn't understand anything and by the end of reading the chapter, she got it, like it was not a terribly big challenge for her.

I've seen that over and over again, that the parts that might seem dense and theoretical are not necessarily as hard as people might presume just by seeing certain words. I think that you have to be able to translate critical discourses in a way that people understand because what's the point of critiquing, if you don't know the language of the critique? What's the point of it if you if it just means gibberish?

Then similarly, by bringing in artists to talk about how their practices relate to this book, how they're making myth, how they're using myth, how their sense of themselves, their self develops, I think it also made it really clear for audience members.

My main thing is that I think these critical academic discourses are important and I think that they can change how we think and I think that the language they introduce changes how we think because the words we use affect how we think. I mean, if I think in these words, my thoughts are not the same if I think in other words. And a lot of queer theory and a lot of feminist theory is trying to challenge things that feel natural to us, because we've rehearsed in such a way for so long, that they become true or natural or real for us in a way that certain critical discourses can blow up and expand upon and challenge.

And I think that it's not something that I can digest for other people, like you have to engage some of the quotes, you have to engage some of the writing; it does take work to think differently and to live differently and to make differently. So I'm trying to really balance like, allowing different levels of entrance into the book but not assuming that an audience can't do the work. I think there's a level of condescension sometimes in some queer theology and some trans theology that's like, if this isn't the simplest language, then it's worthless. And I'm like, simple isn't bad, but simple isn't good. Like it's a neutral way to describe something. But I do think that the ideas that I want to engage with aren't necessarily always simple, and if it's not going to be simple, it takes time to understand and it takes words and explanation.

I hope it doesn't come across in like one particular religion – it's not one religious tradition. I mean, it's very pagan in a lot of ways but there's a ton of engagement with Christian ideas, with Jewish ideas, with Greek pagan ideas. And I think that also speaks to audience: you don't have to believe a certain creed. Because a lot of it's about playing and reimagining and if you don't like the cosmology I put out, if you don't like the dragpoetics or any of that stuff, that's fine. Like, make your own though, or work with someone else to make a new one. And I think anyone can do that. Regardless of discipline.

AD: Let’s talk about Mary Daly, who many might recognize as a controversial radical feminist. There can be this quick impulse to “cancel” any scholar with such inflammatory views, and while you’re obviously critical of her, you recognize the value in engaging in this generative, helpful way rather than simply dismissing her work.

MBK: In the context of theological seminary, we read Mary Daly as one of the key 20th century feminist theologians; we read Beyond God the Father [Towards a Philosophy of Women’s Liberation, 1973], and for all the things I feel about Mary Daly, I think that book is pretty amazing and powerful.

We read out the letters between Daly and Audre Lorde in a spiritual formation class, and our professor has talked about how there could have been an option of reconciliation and understanding between the two, both women who are very angry for very real reasons in their lives.

And that really resonated with how I feel about trans discourse and trans exclusionary feminism because I don't think we would have a lot of the understanding of trans that we do have, and a lot of the discourse that we do have, without feminism. And I don't think that they are separate and I don't think Radical Feminism is useless. I think very much the opposite, that it's deeply necessary in a world that is still patriarchal, in a world that is not radically changing in a certain political way.

Radical feminism, right in the title, is about restructuring society. And I think that a trans discourse that isn't interested and trans politics, that isn't interested in restructuring society, fundamentally, will never be liberation or for us, it will never yield the kind of self-actualization and communal freedom and all those kinds of things that we need it for radically changing how we think about the world.

That desire to connect across time, that desire to make a mythopoetic impact in the world, the idea to change the world through spiritual mythic symbolic language, led to that first paper, "Transcending the Real," and that led to me diving down these different kinds of rabbit holes.

AD: Two of your audiences – which can overlap – are queer people and religious studies scholars/theologians, and I’m thinking about how a lot of queer people have this knee-jerk reaction to anything religious, and your book seems to be contributing to this conversation about, do we expand these existing religious institutions to be queer-friendly, or do we reject it all together?

MBK: There's no reason people shouldn't be mad at organized religion. But I think that there's a particular onus on certain forms of Christianity in particular, especially in the US. Being Jewish in a very Christian country, it’s very obvious to me that plenty of ideas that are considered secular and liberal are very Christian.

At the same time, I think that we are in a moment where people are really invested in spirituality, if not religion, and yeah, there's the term “spiritual but not religious,” which I don't use because I think it's annoying – but I do think it speaks to desires that are pretty rampant in the world that we're in. I mean, the amount of people who are obsessed with Tarot and astrology and UFO sort of ideas, we're in like another boom of psychedelic interest. I think all of these speak to needing to be in a more religiously minded or mythically minded or symbolically rich world and a world that is more alive – because I think the world is alive. Like I think if we're going to talk about reality, I do believe that life is permeating everything. But I also think that if we have a worldview that deadens everything, and if we interact with everything as if it's dead or controllable, it's violent that we are treating it as not alive, but it does functionally make many things – rocks, trees – not alive, and things that we shouldn't be relating to as dead.

So this book is really a little bit of a Trojan horse: we're gonna talk about radical liberation and politics. It's really a book on spirituality and on how to nurture our selves and communities and our cosmic selves and think cosmically in the world. But without separating it from questions of oppression and identity.

What we think reality is, is also constructed by people with specific identities and backgrounds and histories and ideologies. And so if we are just talking about identity and not talking about what reality is, if we're not talking about what the universe is or what the world is, or what cosmos is or how we relate to, if we're not transforming that, then who the hell cares if this new identity can be free or gain rights if a new idea of another identity comes up, and we haven't articulated that, right?

I also think that we're in a time with religion, and some of the not just disbelief but disengagement from not just religion, but some levels of community engagement. I mean, there's a lot of alienation; the pandemic is a form of alienation where literally, like, proximity to people is seen as dangerous. This alienation permeates our society and I think it has a lot to do with Protestant work ethic and ideas of the soul as this unique identity that belongs to everyone individually. And so I think that there's a certain level of responsibility that people need to take to reunify the world, to reinvent the world to engage the world and with a cosmic lens, with a communal lens, with a playful lens.

I think that part of the point of the book is, if we want the world to be different, we have to make it different. I mean, that seems hokey, but it's true. We have to think differently and live differently and play differently. And that means that we can't just reject the religions we've inherited. We've got to work with them, I think, to live in this world better, and to act better and to be able to share our experiences on this level that myth gets to, that other forms of communication don't – this level that combines individual and communal, that combines the real and the imaginary, this level that is hybrid and deeply penetrating this idea of symbols that live within us and through us. And I think that if we're not working in that mode ever we're not going to affect each other in our world in a way where we will just perpetuate the myths we've already inherited. And do that mindlessly.

AD: I’m thinking about the ways people might interpret the term “myth” – I definitely see this colloquial use where people will refer to the “myth of the American dream” or the “myth of capitalism” to make a critique of the permeating, hegemonic propaganda that creates the impression that capitalism or the American dream is reality, or the only truth, and gives us a worldview that goes against our greater instincts. In what ways does this colloquial usage relate to how you are using mythology, and why is this term so important?

MBK: This term that is used in ancient times to talk about the most fundamental truths of the world becomes the word for lies. I think that is deeply weird and creepy and problematic, but that has happened. How can one word mean sort of a truth beyond history or beyond even the kind of ultimate truth thing that is almost truer than our lived experience? And then how can it flip and mean the exact opposite?

I’m using the term in not unlike the way we might reclaim “queer”: there is a sense of accepting or understanding that that term has been used in ways that means unreal, and part of what I'm doing in this book is saying, yeah, maybe it is unreal, because maybe the particular reality that we're in is not good. Maybe the particular reality we're in is dangerous. The particular reality we're in is problematic. And so I think that the commentation of myth as something that is unreal then becomes useful in my own work. But it's not only that, because it doesn't mean it's opposite, it doesn't mean what is most real, doesn't mean what is most significant.

Myth doesn't mean “good,” like, there are bad myths. We can look at myth of capitalism: if you're looking at myth as something fake, and if we're saying fake or something that's constructed – which is not what I would argue, but I think that is what people mean by “their gender is fake, identity is fake” – this is all fake. What they mean is that it's constructed. It's not born, and it's not essential. Construction isn't the same thing as fake. And I also just think, the idea of the myth of capitalism just shows how powerful myth is, right? That myth can structure an entire world and destroy an entire world right? A well-used myth can bring life into being and can destroy life. A well-used myth can orchestrate the actions of billions of people for good or for ill.

AD: You talk about myth as “powerplay”, and clearly your book is invested in creating possibilities beyond our oppressive reality, reaching liberation. Your drag troupe House of Larvae created this piece responding to the Brett Kavanaugh hearings, which I think was a great example of using absurd performance to make meaning from an absurd political moment, and this is art that could be labeled “political” or something. When it comes to social change, I think art is often dismissed as symbolic, relegated to this other category outside of the “real work” of activism or advocacy or organizing. I think your book is really inviting us to see our own or other’s art as a kind of world-making, that isn’t not “political”. What do you think of this exhausting dichotomy or tension between art and activism?

MBK: I think art is fundamentally one of the most profound ways of changing consciousness – both looking at art and making art and being an audience, being a participant, having a different relationship to creativity and what others have created.

Art is that space where it's multi-sensual, right? And I think that's important for activism. Art is about putting a lot of energy into things that are not always money, lucrative or productive. You can spend five hours on a dance and then when it's over, what's the product? I think that that's part of the damaging thoughts about art.

I think it's reflected in certain ideas about what real activism is, because I think people think it [needs to] follow an instrumentalist, capitalist idea of cause and effect. That phrase, “direct action,” to me, is just like so tied to the idea that something's only alive or something's only an agent or something is only powerful if it forces something to do something immediately. Like the idea of power as being something that is with agency forcing something with less or no agency, you have an effect. And I think that part of what happens with sustained art practices is that you become much more the effected-upon thing, then, and there's a fluidity between, you know, if I'm drawing something, there's a connection between what I'm looking at and my hand and my eyes, and there's a back and forth and an intimacy.

AD: We have this culture of ongoing, fast-paced news cycles, and many artists, or anyone, might feel this pressure to constantly react and respond to these spectacles, these crises. How can myth help us navigate that, or what can myth do what other forms can’t?

MBK: Remythification is this process of making more meanings. Allowing more and telling a story or getting an artwork or writing a text with some sort of intention or leading to the effect of having more interpretation possible. Versus the process of allegorization, which is making that one allegory the dominant or only feasible way to understand the meta text.

So when it comes to responding to things in the news, I think that's part of that right? Are we doing remythification or an allegorization? Are we responding in such a way that this act would have no meaning outside of the direct conversation with a particular event in a particular location or does this have meaning that transcends the particular moment, that can make sense in other contexts with different audiences?

How are we thinking about it in relation to the future into the past? Are we saying something about this current moment, to be clear about what it is now? Are we trying to use the current moment to rethink the past and to reap what the future might be?

I think that in the case of the Kavanaugh performance, there is a desire for us to have audience be unhappy with that ending. How does that get an audience to think or act. It’s using the current event to transform what an audience might be experiencing and to agitate.

AD: Why is this “advocacy of the many” so important right now? How would you apply the concepts in your book to the recent rise of fascism and attacks on bodily autonomy, from trans rights to abortion?

MBK: Multiplicity has a lot to do with the fact that, you know, you create a new identity and you advocate for a new identity and then maybe that group of people who ascribed to that identity, do you get a certain number of rights so then the right has to find a new group to go after. And I think that it follows a kind of train of thought of, if what we're doing is saying there is a right way to be, there's a really correct, right category of human that deserves dignity. And even if we keep adding to that category, we're not really switching a paradigm of thought, right? It doesn't necessarily change our way of thinking about what rights are, what humans are, what freedom really is. It's a kind of, I don't know, call it democratizing of, I think, what it means to be a person if we're accepting that all people are multiplicitous.

People who are scared of trans people, who think that someone else transitioning is a threat to their identity – I agree it is a threat. To some extent, it's a threat to a worldview. It's a threat to a worldview oof gender essentialism, which is just an extension of any sort of self-essentialism. My whole worldview is shattered, which also means the class that I'm born into, doesn't get to be my birthright and that means that the rights that I was born into could be taken away. And the life and beliefs that I've inherited, you know, are not static and are not given and holy shit. That makes me scared and angry.

I do workshops with more progressive but diverse groups, Protestants and Catholics. They’re movement-based workshops that are about attuning to our own gendered autobiographies and looking at using movement and sort of somatics and free writing.

So people might be encouraged to think about times in their lives when they were told they couldn't do something because of their gender or something that they were told they should do because of their gender. When do you feel pleasure? When do you feel joy? And then how does that relate to these questions of gender and sexuality? And people create gesture movements based on these kinds of questions, and then they teach other people these gestures and movements and suddenly one person's gender biography that orchestrates the movements they're doing in this space become shared by another person. And then that duo shares what they created with another duo. And it's this movement from internal experience and gesture to a shared experience of a shared collective history of gender. It's something that speaks to people who are not in the queer theoretical world at all.

This is the kind of workshop that I do that is informed by the multiplicity that I write about in The(y)ology. It's the sort of thing where the book can't be the only way to do this work. But it can be a really helpful resource for how a facilitator or an artist or an organizer might think about what they're doing when they bring ideas about gender and sex into a space where that might be difficult. It's an approach that's not invested in what's the correct terminology or the identities. Rather, it's an approach of, what are the stories that we have lived through and that live inside of us and how do we access them and how do we share them? And how do we do it in a way that can be joy giving in a communal space and healing in a communal space?

AD: Another really significant audience for this book is folks in environmental studies, environmental humanities – there’s so much in here that can help us work through our embedded dichotomies between nature and culture, and categories of natural/unnatural. How do you think your ideas can be applied to environmental thinking, environmental concerns?

MBK: The subtitle of the book might as well be “mythopoetics for eco liberation.” Part of the book is looking at our cosmic selves and looking at ourselves as planets, and planets that are just big ecosystems that can be broken down into smaller and smaller ecosystems.

And if we're thinking of gender as this word thing or this soul thing or this thing that isn't a system of entities interacting – then I feel like that's another human cut away from nature.

I critique the idea of nature throughout the book, I mean, the word “nature,” because I think that you know, similar to some of the critiques of Anthropocene, it perpetuates this human and world divide, this human/nature divide. I think that this book is a challenge to some of that but using art and beauty and humor to do that, and pornography and dance and music.

[The book is] a suggestion to any sort of identity politics or any sort of identity movement, to remember that this is always a question of world. This is always a question fundamentally of how we relate to the world. And any sort of identity or social or civil rights, politics that doesn't root itself and ecology to me is ridiculous. We can't be liberated in a world on fire.

I also think that the issues that affect trans people and gender non-conforming people and all people – anyone who has ever had a sex or a gender or conflict or ambiguity – has been affected by the sort of ideologies that lead to climate catastrophe. Problems in nature [for] biology or many medical fields start in addressing things that are less controllable or less normative and trying to find a way to taxonomize and hierarchize.

Subject/object paradigms, maybe it's reductive, but that is the fundamental oppression: that there is an active, gentle state of being and a passive, dead state of being and that one always does something to the other. And I think any kind of oppression can be traced back to that to some extent, some form of that.

I think that myth can be a powerful way to get past some of that. Performance can be a way to relate to the world differently.

Some of the best queer mythopoetics that I've observed is Beth Stephens and Annie Sprinkle’s Assuming the Ecosexual Position: The Earth as Lover. [It’s] so queer and so environmental at the same time and uses the model of a wedding, marriages to Earth in this like radical, queer way, including having people who participate who decry how horrible weddings are. And these are non-monogamous weddings to the earth and like these, this way of relating to the earth. They bring humor and sexuality and play into their environmentalism.

I think that some of the issues around objectivity and seriousness that can lead to static thinking and a rigid worldview are a big problem in some ecological writing. And I think that we also know that people tend to care about things in illogical ways. People tend to care about things that they feel a relationship with. And all of our relationships hopefully have different levels of emotional connection and mood. I can't imagine having a lover who I never smile with, never feel for and never delight and find humor in. So why should we feel that way about the Earth? If we don't have that range of experience?

I've been a little more resistant to some of the transhumanism or post humanism stuff that I was more invested in or encouraged by when I was writing The(y)logy. I'm more neutral to that now and I think part of it is that I don't think we have to get rid of the category of human or the or humanism to not be anthropocentric. I don't think valuing what is human has to be Anthropocentric.

We need to do this and this and this to combat change in climate, different climate catastrophes, situations and different parts of climate change. We're in that mode, but we also can think with trees and water and birds and snails and fungi. Like there's a way that we can think with our decomposing ancestors and tap into what I would call the cosmic vision. We have to think cosmically, and to do that sometimes we have to do it logically. But I think ultimately, the best way to think and maybe the only way possibly to truly think cosmically is outside the realm of logos.

Maybe in some ways The(y)ology is a social interest book, you know, it's about queer and trans liberation. It might seem like it's primarily talking to the specific needs of a group but I feel like that's the Trojan horse of the fact that it's a cosmic revisioning of how we exist with the world. How do we understand world and our place in world and how we experience world and how world experiences us? And those kinds of questions to me always have to be part of ecology. We cannot do an ecology that reduces the world to a thing we can steer in a particular direction.

Support the author by purchasing The(y)ology: Mythopoetics for Queer/Trans Liberation through the publisher, Punctum Books, or ask your local bookstore to order! The book is also available via Open Access on JSTOR.