Utah Lawmakers Tried to Pass a Mask Ban. Almost Overnight, Utahns Resoundingly Rejected It.

At the beginning of a busy Utah Legislative session that would ultimately include bill proposals attacking trans rights, public sector unions, abortion, and mail-in voting, among other issues, another repressive bill almost slipped under the radar: amendments to criminal justice policy in HB312 included language that would criminalize masks.

The original text of HB312, which was introduced on January 23, proposed to “create[s] a criminal offense for the intentional concealment of identity in a public gathering,” making it a class B misdemeanor if someone “wears a mask, or other facial obscurant or disguise; and (b) does so while congregating in a public place where other individuals are also masked, facially obscured, or disguised.” In Utah, a class B misdemeanor can be penalized with up to six months in jail, a fine of up to $1,000, or both.

Utah COVID justice advocates had been watching for the state to propose similar legislation. The last year has seen a wave of mask bans being proposed or enforced across the country, in an alarming confluence of backlash against pro-Palestine protest and COVID emergency era public health measures. In June 2024, following campus protests nationwide against the ongoing genocide in Gaza, the North Carolina Legislature passed a mask ban; in August, New York’s Nassau County passed a mask ban, while the University of California system president announced the entire campus system would prohibit “masking to conceal identity.” Some places, such as Louisville, KY, have announced they will begin enforcing their state’s existing anti-mask laws. Other places where officials are promoting mask ban proposals include Chicago; Los Angeles; New Jersey; New York City and State; Ocean City, NJ; Philadelphia; St. Louis, MO; and Texas.

Utah’s proposed mask ban, sponsored by Republican Majority Whip Karianne Lisonbee, posed many concerns for Utahns. Many saw it as criminalizing a crucial tool for people to protect themselves from not only airborne pathogens such as COVID-19 or the flu, but also from the state’s uniquely poor air quality, as well as attacking rights to privacy, free speech and the ability to protest, or gather at all in public.

Days before the bill was scheduled to be discussed in committee on February 3, community groups and individuals spoke out against the bill on social media, encouraging others to contact their legislators to oppose it. Many of these groups acted without awareness of each other — but the impact was clear: legislators were overwhelmed enough by their constituents’ dissent to remove the proposal before it reached committee discussion. While the committee approved other amendments in HB312, Utahns were relieved that the mask ban portion had been removed.

SLC COVID Education, a mutual aid group that distributes free masks, tests and education in the Salt Lake City area, posted about the bill on their Instagram account’s story soon after the bill was released. A few days later, Utah Physicians for a Healthy Environment, a group of scientists and concerned citizens advocating for air quality, opposed the bill on their social media and in an email to supporters. Less than 48 hours before the committee hearing, Kai Akina, co-founder of the mutual aid and community group Anti-Cult Cult, shared a toolkit with legislators’ contact information and sample language people could use to oppose the bill. This toolkit was shared by groups including COVID Safe Utah, Healthcare Workers for Palestine’s Salt Lake City Chapter, RevLoveMedia, and queer-owned bookstore Under the Umbrella, which requires masks. Another toolkit was shared within the private Still COVIDing SLC/Utah Facebook group, and a group of COVID-cautious parents also drafted their own letter to send to representatives.

Utah’s proposed mask ban was broad, defining “public place” in a long list, including areas commonly thought to be private: “streets or highways; and the common areas of schools, hospitals, apartment houses, office buildings, public buildings, public facilities, transport facilities, and shops.” The ban was also vague, leaving out the specifics of how a mask wearer’s intention would be determined.

Masks & Disability, Health, and Infectious Diseases

Utah’s proposed mask ban contained no exemptions for medical concerns, and even included common areas of hospitals — spaces where people might be actively contagious with COVID or any airborne illness. When many hospitals have made masking optional, and many medical providers are already hesitant or refuse to wear masks to protect patients, many Utahns were concerned this would make medical spaces even more unsafe — and prevent anyone from protecting their health in any public setting.

Nate Crippes, Public Affairs Supervising Attorney at Utah Disability Law Center, immediately recognized the bill’s dangerous implications for people with disabilities. This proposal “means that people with disabilities that need to protect themselves by wearing a mask now have to fear criminal charges if they congregate with others who need to wear masks or those who wear them to protect their loved ones,” he said.

For Utahns like Maeve Hall, who has leukemia and is immunocompromised, this bill would have threatened their ability to access life-saving care, as well as gather with anyone safely for any reason. “I have to make sure the only places I go are with other people who mask,” she said. “I’ve been especially concerned about COVID because dealing with Long COVID symptoms while going through chemotherapy would be even more painful than it already is.”

For Sav Pearson, who has been disabled by Long COVID since 2022, masking is a vital everyday practice to protect themself. Long COVID is an umbrella term for a complex — but not rare — chronic condition with a wide range of symptoms, ranging from mild to severe, that can develop after acute COVID infection.

Pearson’s Long COVID symptoms include brain fog, post-exertional malaise, chronic pain, and chronic fatigue that can be triggered by physical, emotional, or cognitive exertion. Their doctors warned reinfection could likely worsen their symptoms, and they recommended masking among other precautions.

“If I were not able to mask in public spaces, I would not feel safe in those spaces. Banning masks is ableist discrimination against folks with disabilities and chronic illnesses,” Pearson said.

According to the Utah Department of Health and Human Services’s first report on Long COVID in the state, released in August 2024, 1 in 12 adults have experienced Long COVID symptoms. Because there is currently no biomarker for Long COVID, and the condition is often dismissed or misunderstood by providers, this number is likely an undercount. While some underlying health conditions are shown to increase the risk of developing Long COVID, anyone can develop it regardless of any existing conditions. The only way to prevent developing Long COVID is by avoiding COVID infections — and wearing an N95 or KN95 mask is one of the most effective tools to do so, as part of a layered approach including vaccination, air filtration, and avoiding crowded areas.

Although the proposed mask ban, as written, suggests people would not be criminalized for wearing a mask if they are the only one to do so in a public place, this logic cuts against scientific consensus that masking to prevent transmission is most effective when many people do it. Banning masks would make it more difficult for those already living with the condition to protect themselves from further damage, while stigmatizing a crucial tool for avoiding Long COVID in the first place.

When the federal COVID emergency protections expired in 2023, this marked not the biological end of the viral threat, but the end of the government’s willingness to fund systemic and comprehensive public health support that many Americans relied on. Since then, data has shown that COVID transmission has remained a persistent year-round threat. Without systemic public health measures to prevent transmission as well as care for those who are sick — such as widespread air filtration, guaranteed masking in health care settings, paid sick leave, free PCR tests, or accessible treatments — all Utahns are left vulnerable to repeat COVID infections. COVID infections can be deadly; the Utah government has reported more than 5,000 COVID deaths, though accurate data is not available after November 2023. Repeat infections are shown to increase the risk of developing Long COVID, and even COVID infections that appear mild in the acute stage are shown to damage the brain and other organs.

“One of the things that is not truly communicated enough is the underlying danger that everyone has — all ages and all health conditions — to have organ damage and Long COVID,” Yaneer Bar-Yam, pandemic expert and co-founder of World Health Network, a global group of scientists advocating for COVID protections, including against mask bans, said. “The entire society is being affected in very strong ways.”

“Had this bill [gone] through, I wouldn’t feel safe in public anywhere,” Hall added. “I can’t take off my mask, and I [wouldn’t be able to] be around other masked people. Protests, community gatherings, outings with friends — at any moment I feared I would risk getting arrested or harassed by police to ask about the intentions of my masking.”

For MacKenzie Bray, Executive Director of Salt Lake Harm Reduction Project, these contemporary mask bans are part of a legacy of ableist policies. “It harkens back to Ugly Laws that were enforced throughout the 17th and 18th century in the United States — laws that limited or banned disabled and poor people from essentially existing in public,” she said.

Some Utahns were worried this bill would even prevent surgeons from wearing a mask during surgical procedures. “As a person who spent most of his 40-year career in the operating room wearing a mask, [a ban] is utter nonsense,” Dr. Brian Moench, Executive Director of Utah Physicians for a Healthy Environment, said. “All the people who have to wear a mask in an operating room didn’t end up committing more crime.”

Though it’s possible for a mask ban to include medical exemptions, this can create more problems. For example, while the Nassau County mask ban does include exemptions for religious, medical, or cultural reasons, it’s unclear how those exemptions will be determined and enforced. According to reporting from Mother Jones, police received inadequate training on how to enforce the new law, and NYC Liberties Union experts noted that police are not allowed to interrogate someone about their private health information, making it impossible for police to independently determine whether someone is wearing a mask for health reasons.

Even if the Utah bill had included an exemption for people with health conditions or disabilities, opponents say that’s not enough. Requiring that type of documentation would exclude anyone who can’t access such a diagnosis, such as from not having access to health care. It would also exclude anyone, regardless of health conditions, who masks for other reasons, such as to avoid Long COVID, or any illness, or passing illness on to others.

“The fact that anyone can be threatened by COVID, and that simple actions can be taken to help mitigate some of that — it's hard for me to fathom why they wouldn't be willing to take those steps to protect themselves,” Vanessa Sun, founder of the Still COVIDing SLC/Utah Facebook group, said.

“I cannot afford to get COVID in the first place. I don’t have the money to take two weeks off of work, and I do really care about not spreading it to my community,” Leo Lynn, co-founder of SLC COVID Education, said.

Utah’s proposal to ban marks a significant reversal of previous scientific consensus used to address the COVID pandemic, though it does reflect the state government’s reluctance to require masking since the beginning of the pandemic. Utah did use mask mandates during the emergency era — and a peer-reviewed scientific study found that mask mandates enacted at the state, county, and local levels in 2020 and 2021 in the state effectively reduced transmission, a conclusion that has been repeated in several countries. These results underscore the need to address a systemic problem such as a pandemic with systemic, rather than individual, solutions. Utah saw several protests against mask mandates, and some legislators echoed the protestors’ message that mask mandates infringe on individual freedom.

“The mask requirements, the pushback on that was that it’s an infringement on bodily autonomy,” Lynn, of SLC COVID Education, said. A mask ban would remove even that level of individual bodily autonomy, in effect codifying the freedom to infect others — without the freedom to protect from infection.

Masks & Environmental Air Pollution

The bill’s intention to criminalize masking in both indoor and outdoor places appeared to pose a significant barrier to Utahn’s ability to protect themselves from air pollution, which has become a year-round public health threat.

The Salt Lake Valley experiences some of the worst air quality in the country, due to winter inversion, ozone exposure, and wildfires, while Southern Utah is plagued by regional haze. And air quality is on track to get worse, due to the receding Great Salt Lake. As the lake recedes, toxic metals on the lakebed such as arsenic, copper, and lead become exposed to the air, able to be transported across the valley by wind storms. It’s estimated that the Great Salt Lake generates about 15 dust storms a year, compared to none 15 years ago, though the state needs more equipment to collect comprehensive data. Studies have found that most of this lakebed pollution impacts residents on the West Side, who are majority communities of color, and already experiencing worse air quality in general in Salt Lake Valley. When inhaled, these metals are known to cause short-term and long-term health complications.

KN95 and N95 masks can filter out the harmful particulates of air pollution, in addition to airborne pathogens. Because of this poor air quality, masks have been part of public life for many Utahns long before the COVID pandemic began. At the first rally for clean air at the Utah State Capitol in 2014, for instance, N95 and KN95 masks were not uncommon in the crowd of several thousand people.

“The ability to wear a mask to protect myself — I feel like it’s integral to every Utahn. We just have a special circumstance where the air quality is so poor,” Franque Bains, director of the Sierra Club Utah chapter, one of several nonprofits that advocates for better air quality policy, said. “Anybody bringing up a conversation on whether or not we should have a ban on masks is really disconnected from the needs of a community. A mask is a tool for health, whether that’s to protect from airborne illnesses or viruses, and also to help deal with air quality.”

Akaysha Greer, who lives in Utah County, had been masking since before the COVID pandemic to protect herself from poor air quality. Now, she also masks to protect herself from infection, which would worsen her Chronic Active Epstein Barr Virus symptoms. She founded COVID Safe Utah in 2023 to help connect people who are still taking precautions, and urges everyone to care about masking, since anyone can become disabled by an infection.

“Folks don’t have to be immunocompromised or chronically ill to care,” she said. “These bans are very ableist, and they’re a critical danger to everyone. They enable eugenics, and that should be a major concern to everyone, as eugenics is something that can affect us all, and does affect us all.”

Exposure to air pollution also increases the chances of COVID prognosis. While many tools to protect yourself from air pollution and airborne disease overlap — such as masking and air filtration — COVID emergency-era mask mandates have contributed to stigma against these tools.

Still, organizations such as nonprofit Salt Lake Harm Reduction Project and grassroots group SLC COVID Education continue to distribute free masks, tests, and COVID information to meet ongoing community needs. Salt Lake Harm Reduction Project distributes free masks and COVID rapid tests with grant funding from the Utah Department of Health and Human Services. SLC COVID Education has distributed more than 3,000 free masks across the Salt Lake City area since last fall. “There are a lot of people who want to mask,” Lynn said.

Despite the overlap, Lynn sees a double standard around masking after it became politicized by COVID policy: “It’s smart to mask for air quality, but you’re [seen as] paranoid if you’re masking to prevent yourself from COVID.”

The absurdity of this dangerous politicization of public health tools was highlighted when wildfires broke out in Los Angeles in January. Less than a week after Los Angeles Mayor Karen Bass had proposed a mask ban for the city, in June, she tested positive for COVID. Months later, when the city didn’t have a big enough stockpile of masks during the wildfire, members of her staff reached out to local mask bloc organizations asking if they could provide thousands of masks to protect residents from harmful wildfire smoke, which they did.

For Pearson, who lives with Long COVID and leads local organizing efforts to protect Great Salt Lake, the issues are not separate. They and other Great Salt Lake grassroots organizers are helping to create a culture of masking in those organizing spaces. During monthly gatherings at the shores of Great Salt Lake, attendees mask while in close proximity to each other.

“The drying Great Salt Lake constitutes a mass disabling event,” they said. “Everyone who lives here is at greater risk for asthma, cancers, and other effects of poisoning. Masks are important for all of us to protect ourselves from the state’s negligent approach to this crisis and its failure to mitigate industrial harm.”

Masks & Protest and Privacy

For many Utah social justice organizers, the intentions of the proposed mask ban legislation were clear: to quell public protest and free speech by preventing people from gathering safely — and to weaken opposition by exposing the public to repeat infections.

Many kinds of in-person rallies, marches and protests can be important (though not the only) ways to resist oppressive conditions and organize for a better world. While the rights to assemble and practice free speech are guaranteed by the First Amendment, outdoor crowded protests can spread disease, and put protestors at risk of the harms from air pollution. By proposing to criminalize masks, Utah’s bill conflates masking with danger, when in reality, even stigmatizing masks makes public life less safe for everyone. If Utahns do not feel safe — or able-bodied enough — to attend in-person protests without a mask, that route of democratic public dissent becomes more difficult.

“This is a move to violate First Amendment rights to protest and to intimidate individuals with fear of criminalization,” Bray of Salt Lake Harm Reduction Project said. “If immunocompromised people risk criminal penalties just from wearing a respirator during a protest, including legal ones, then Rep. Lisonbee is in action criminalizing being sick.”

“The state legislature is trying to create conditions that make protest less safe for disabled/chronically ill people and for everyone else,” Pearson said. “That is unconstitutional. It also won’t work. Protest has always been unsafe for BIPOC and Trans folks because of Utah’s history of racism, transphobia, and police brutality, but communities keep showing up. Protest is already unsafe for disabled/chronically folks because the air is so polluted. But guess what? The most courageous activists I know here are BIPOC and/or disabled. We’re not going anywhere.”

By framing masking as dangerous because it conceals identity, this bill would also remove protestors’ right to privacy, subjecting people to increased surveillance, explained Jay Stanley, senior policy analyst with the ACLU Speech, Privacy, and Technology Project. Facial recognition technology and other surveillance has become increasingly widespread, from cameras installed in and around private businesses, to detailed photographs of a protest crowd. Stanley also says hats and sunglasses already conceal identity more effectively than medical masks — and during the early stages of the COVID pandemic, facial recognition technology was improved to better recognize faces underneath masks.

“[Mask bans are] always motivated by dislike for one particular viewpoint people are expressing. It's just so narrow and short sighted and ignores the people's individual rights,” Stanley said. “We can't have government officials deciding what views can or cannot be expressed in public.”

“The public stigma of wearing a mask and interpreting a person’s political leanings based on whether or not they wear masks, that’s extremely unfortunate and detrimental to society at large,” Moench, of Utah Physicians for a Healthy Environment, said. “Mask wearing should be looked at as, in some circumstances, a civic obligation.”

Mask bans are not new — and their history demonstrates how they have been selectively enforced to target and repress particular groups’ views. New York’s first ban, which dates back to 1845, targeted tenants dressed up as Indigenous people to rebel against landlords. Several Southern states passed anti-mask legislation in the 1940s and 1950s to target the extremist hate group Klu Klux Klan.

“The KKK history obviously makes the right to wear a mask complicated for people,” Stanley said. “But I would note that a lot of the enforcement of mask laws has been directed against Black Lives Matter protesters in a very selective fashion…A lot of those KKK mask rules were not promulgated by people who supported civil rights, but they were promulgated in the south by supporters of segregation, who thought the KKK was making the quote-unquote modern segregated south look bad.”

In recent years, mask bans have been selectively applied against not only Black Lives Matter protesters but also a range of others, including Occupy Wall Street protestors, anti-racism protesters, and police violence protesters.

This time, legislators supporting similar mask bans in the past year have explicitly stated that their mask bans are targeting pro-Palestine protest.

Jews for Mask Rights, an advocacy group founded in New York to oppose mask bans, wrote an open letter rejecting the false conflation of masking with antisemitism, an alarming extension of falsely conflating pro-Palestine protest with antisemitism.

When University of Utah students and allies organized a pro-Palestine encampment in April and May 2024, many wore masks, and at least 20 demonstrators were arrested. If passed, the mask ban legislation would have added an additional criminal charge to punish this type of protest, which was already met with intense police brutality including the use of rubber bullets.

Healthcare Workers for Palestine’s Salt Lake City Chapter has organized vigils and other events in solidarity with Palestinians resisting the ongoing genocide, and encouraged or required masks at all of their events. Ambreen Khan, a healthcare worker and the chapter’s co-founder, said that if this mask ban had passed, it would have been all the more important they kept masking.

“Solidarity with the Palestinian people is very intersectional,” she said. “I feel very strongly that [the mask ban] is a segue into taking away more and more rights and chipping them away. It is all part of the same puzzle, which is the right to self determination, whether that’s for the Palestinian people, whether that’s for people here locally.”

Beyond threatening the right to protest, Utah’s bill also has dangerous implications for anyone’s ability to be in public for any reason. The bill did not differentiate between a medical mask, such as a KN95, N95, or surgical mask, and other types of masks or facial coverings such as hijabs, niqabs, burqas, scarves, or bandanas. The only exception included in the proposed bill was a “Halloween activity or celebration, a masquerade party, or a similar activity or celebration.” Many Utahns were worried the wide reach of the bill would embolden surveillance and harassment of already marginalized racial, ethnic, and religious groups.

Utahns are already subject to racial profiling by police: A 2021 study analyzing ten years of data found Utah police disproportionately shot at “racial and ethnic minorities.” Nationally, Asian Americans have faced an increase in racist violence often tied to masking, and some studies show Black and brown people are more likely to mask and more likely to suffer poor health outcomes after a COVID infection.

“As a Muslim, there are people who wear the hijab, sometimes it covers your face. And like, would that be banned? That’s an infringement of people’s ability to practice their religion,” Khan said.

Sala Tumanuvao, who is part of a group of parents that take COVID precautions to protect their families, could see how this kind of policy would easily lead to racial profiling. “We could probably get away with still wearing masks in the grocery store, because no one would most likely raise a fuss about that, but for the brown people in our group, me included, they might look for any reason to profile us,” she said.

The Committee Hearing and What’s Next

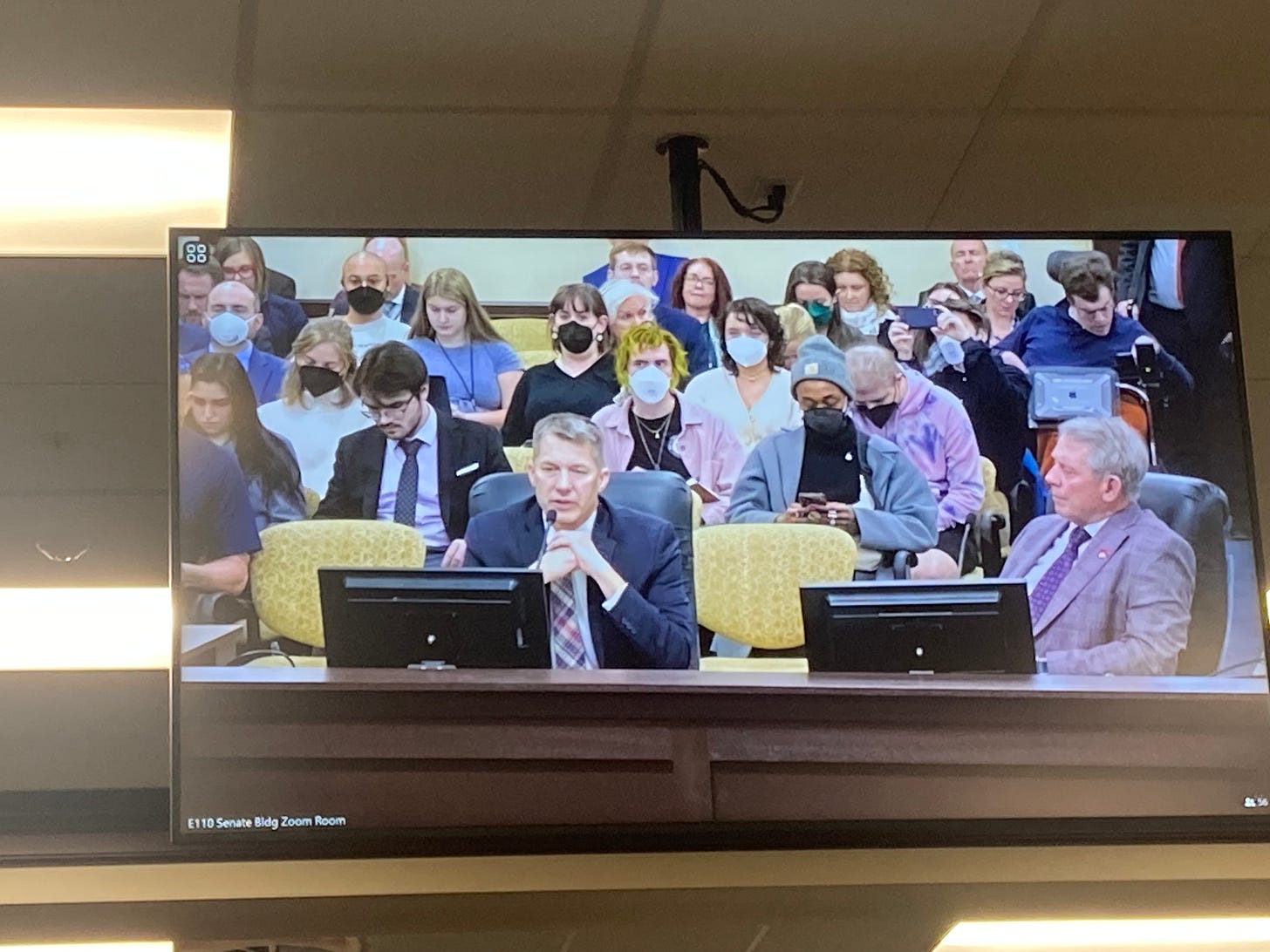

On the day the bill was scheduled to be discussed by the House Judiciary Standing Committee, February 3, several people in masks arrived at the meeting room at least ten minutes early. Masked attendees talked amongst themselves, some drafting the public comment they planned to give; others who opposed the bill attended online. By the time the hearing began, the room was packed, with about a third of attendees wearing masks, most of them sitting on one side of the room.

The Committee would be tasked with reviewing the bill and deciding whether to advance it to floor debates with the full chamber and vote. If the bill passed the House, the same process would repeat with the Senate, and Republican Governor Spencer Cox would need to approve the final bill.

HB312 had been listed as the first agenda item, but because sponsoring Rep. Lisonbee was not present, Committee Vice Chair Republican Nelson Abbott said they would move onto the next agenda item. About 30 minutes after the meeting began, Lisonbee arrived, immediately whispering something to a colleague.

She then settled at the microphone and turned to look back at the audience. “Are you guys talking about a super controversial bill today? There’s a lot of people here today!” she said to a quiet room.

Some masked attendees were expecting a heated discussion. Nassau County’s mask ban hearing had lasted almost seven hours, and many masked attendees were harassed, while mask ban supporters were given more time to comment. Instead, Utah’s agenda item was dismissed in an offhand way.

"For all the people that are here to talk about the masking language in the bill, it’s no longer in the bill,” Rep. Lisonbee said. “So there you go. I tried to email back everyone that emailed me."

Most of the masked attendees barely moved, and most stayed. After Lisonbee moved on to discuss other proposals in HB312, Democratic representative Grant Miller said he “received more emails than I can ski on about the mask ban,” and asked Lisonbee to confirm there was no mask ban language in the bill being considered. Lisonbee confirmed this was true. The updated proposal was not immediately visible on the website, but the mask ban language had been removed by the end of the committee hearing.

After the other HB312 items were introduced, Vice Chair Abbott opened the floor to public comment. But first, he said that as an attorney, there’s a saying that when you’re ahead, sometimes it’s wisest to not speak, acknowledging that many people had come to speak on the mask ban. Despite this discouragement, several masked attendees began their public comments thanking the committee for rejecting the ban, before commenting on the other proposed measures.

“The hearing was really stressful,” Hall said. “But once she got in and immediately said that the mask portion had been completely removed, I started crying in my seat. It was such a relief to hear.”

“People took time out of their day, people who are also vulnerable, to advocate for something that should have never been there in the first place,” Akina, who created one of the action toolkits, said after the hearing. In addition to attendees spending time during the traditional workday, being in a crowded room with so many unmasked people constituted a significant risk of COVID exposure for all attendees.

The outpouring of dissent demonstrated how disastrous this type of policy would be for so many Utahns, while highlighting the many reasons to strengthen coalitions between groups — whether they are focused on public health, environmental justice, or social justice. After all, it’s possible the legislature will try to pass a similar mask ban again.

As part of their efforts to strengthen a culture of masking, World Health Network launched a campaign to advocate for Right to Mask laws. This type of legislation, which has already been proposed in Illinois and Massachusetts, aims to ensure individuals retain this freedom to protect themselves and others.

In November, more than 40 social justice groups nationwide — representing racial, disability, and gender justice organizations — signed an open letter to urge local, state, and federal lawmakers to denounce mask bans, citing concerns for disability rights, bodily autonomy, free expression, privacy and discrimination.

For now, Utahns who opposed the ban urge others to regularly wear a mask — in the more places the better. With the Trump administration rolling back key public health resources, and eroding trust in public health, masking is one action that individuals can take that has immediate potential to reduce material harm, while also resisting ideologically motivated attacks against commonsense public health measures.

“People have a right to protest, and they have a right to feel safe while protesting. This is especially important right now, when fascism is rising and human rights are under attack,” Pearson said.

“I think the biggest reason why we should mask is because we can't fight back if we're sick. And I try and encourage people to mask in their everyday lives, not just to protests,” Tumanuvao said.

COVID and Long COVID remain persistent threats, and KN95 and N95 masks offer vital protection from other airborne pathogens, including those that have seen recent unusual outbreaks, including the flu, measles and tuberculosis. Pandemic experts are also warning of another pandemic if avian flu mutates to transmit between humans.

Not only will masking protect them and others around them from illness and pollution, but it can also help create a shared culture that recognizes masking is here to stay, and is a necessary, collective good.

“I super appreciate everybody in our community working very quickly together, and what they need to know up at the Hill is that our communities are informed,” Akina said.

“We'll keep the pressure on, because it does work, and this does prove that we can make a difference and make change,” Greer of COVID Safe Utah said.

Olivia Stovicek contributed editing to this article.

That’s insane. They’re trying to pass that for someone whose immune system is weak. I can tell you firsthand that mask has helped protect me from all these airborne viruses. I think we should all just wear masks and stand up to the system on this one. They’re gonna do arrest all of us.

Sounds so similar to Maryland’s mask ban proposal! I think it’s both the Manhattan Institute and ADL that’s writing the language for all these across the country: https://manhattan.institute/article/model-legislation-to-modernize-anti-kkk-masking-laws-for-intimidating-protesters